- Louis the Pious

- (778-840)The only surviving son and heir of the great Carolingian king, Charlemagne, Louis the Pious ruled the empire from 814 until his death in 840. As emperor he introduced important reforms of the structure and organization of the empire and continued the religious and cultural reforms associated with the Carolingian Renaissance. Traditionally accused of causing the collapse of the Carolingian Empire because of his excessive devotion to the church and his domination by his wife and other advisors, Louis is no longer blamed for the empire's collapse. Instead his reign and his understanding of his office are seen in a more positive light, especially the first decade, when he instituted a number of far-reaching political and religious reforms. Although the empire did not fall because of Louis but because of fundamental flaws in its structure that had already emerged in Charlemagne's last years, its fortunes did suffer during Louis's reign because of the revolts his sons waged against him.Louis's youth was marked by his early introduction to power. In 781, when not quite three years old, Louis was crowned and anointed king of Aquitaine by Pope Hadrian I. This crowning has traditionally been seen as Charlemagne's concession to demands for independence in Aquitaine, a territory incorporated into the empire by Pippin the Short, but more likely he intended it as an effective means to govern the province and provide practical experience for Louis. Aquitaine did provide important lessons for Louis, who faced revolts from native Gascons and repeated raids from Muslim Spain. Louis effectively responded to both these threats during his reign as king and even undertook counteroffensives into Spain. Although he frequently communicated with his father, Louis ruled Aquitaine on his own and was never visited by Charlemagne in the subkingdom. He also participated in military campaigns outside Aquitaine, including campaigns in Italy and Saxony. Moreover, while king of Aquitaine, Louis had a number of experiences that shaped his later life. In 794, Louis married Irmengard, the daughter of a powerful noble, who bore him three sons and two daughters. He also initiated a program of church reform with Benedict of Aniane. Finally, Louis's future was shaped by his father's ordering of the succession. In 806, Charlemagne implemented a plan of succession that divided the realm among his sons, a long-standing Frankish tradition, in which Louis would continue to be king of Aquitaine. On September 11, 813, after his other brothers had died, Louis was crowned emperor by his father at a great assembly in Aachen.In 814, following his father's death, Louis succeeded to the throne as the sole emperor of the Frankish realm and brought a more profound understanding of the office of Christian king or emperor than his father had had. Like his father, Louis was filled with the sense of Christian mission that his position entailed, perhaps best demonstrated by his expulsion of prostitutes and actors from the imperial court and his dismissal of his sisters, none of whom had been allowed by his father to marry, to religious communities. Unlike his father, however, Louis understood his position strictly in imperial terms, an understanding reflected in his official title: "Louis, by Order of Divine Providence, Emperor and Augustus." Unlike his father who made reference to his royal dignities in his official imperial title, Louis dispensed with royal dignities in his official title from the beginning of his reign and provided a solid foundation for the empire in 817. In that year, following a serious accident while crossing a bridge in which several were injured, Louis held a council at Aachen. At the council, Louis established a new framework for the Frankish empire, whose territorial integrity would remain inviolate. In the Ordinatio imperii, Louis instituted a plan that would have allowed the empire to continue as a political and spiritual unit forever. His eldest son, Lothar, was associated with Louis and would ultimately succeed him as emperor over the entire Frankish realm. Louis's younger sons, Louis the German and Pippin of Aquitaine, would receive subkingdoms-a concession to Frankish tradition-but would be subject to their father and then their brother. This bold new design was rooted in Louis's firm convictions that God had bestowed upon him the burden of government and that the empire itself was a divinely ordained unit.

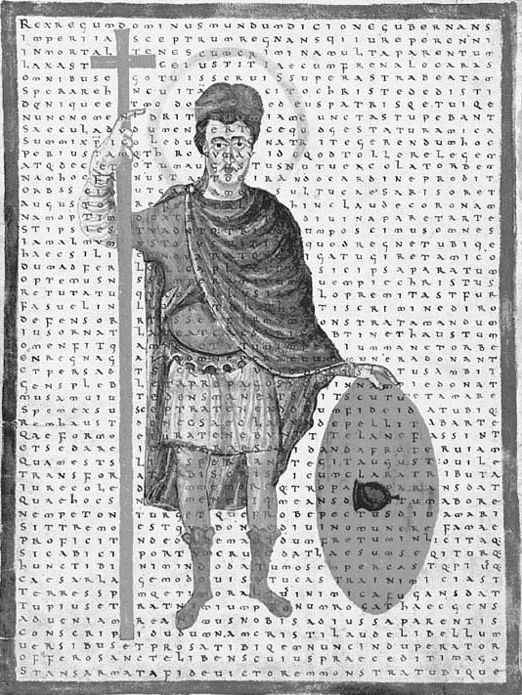

Emperor Louis the Pious in the dress of a Christian Roman ruler from Hrabanus Maurusis (Rome, Vatican Library)Equally important steps were taken by Louis to reorganize and strengthen relations with the pope in Rome. In 816 he was crowned by Pope Stephen IV in the city of Rheims, a coronation that has traditionally been seen as a concession to papal authority and an abdication of sovereignty. Louis, in fact, gave nothing up by accepting coronation from Stephen, but merely solidified relations between the pope and emperor and confirmed what was implicit in the coronation of 813. Furthermore, because the pope was the highest spiritual power and the representative of Peter, the great patron saint of the Carolingians, it was only logical that Louis should receive papal blessing. But more important than the coronation was the new constitutional and legal settlement that Louis imposed on Rome in two stages, in 816/817 and 824. Starting with the unwritten rules that had guided relations between the Carolingians and the pope for the previous two generations, Louis issued the Pactum Ludovicianum in 816 and confirmed it the following year with the new pope, Paschal I. This document identified the territories under papal control and precisely defined the relationship between Rome and the Frankish rulers. Although recognizing papal autonomy, the pact proclaimed the duty of Carolingian rulers to protect Rome. This agreement provided a written basis for the relationship between the pope and the Carolingian emperors and regularized the relationship between them by incorporating it into traditional Carolingian governmental structures.An even greater step in the development of the relationship between Louis and Rome occurred with the publication of the Constitutio Romana in 824. In 823, following a period of turmoil in Rome involving the pope and high-ranking officials of the city's administration, Lothar, acting as his father's representative, issued the Constitutio, which confirmed the long-standing relationship between the Carolingian rulers and the popes. The Constitutio was intended to protect the pope and people of Rome and to provide a clear written framework for the place of Rome in the empire. The Constitutio stated the obligation of the pope to swear on oath of friendship to the emperor after his election as pope but before his consecration. The people living in the papal territories were also to swear an oath of loyalty to the emperor. The Carolingians claimed the right to establish courts in Rome to hear appeals against papal administrators. The Constitutio summarized, in writing, the customary rights and obligations of three generations of Frankish rulers, providing a more solid foundation for the exercise of Carolingian power in Italy.Louis also instituted important reforms of the church in his empire during his reign as emperor, building upon reforms that were begun while he was still king of Aquitaine. With his close friend and advisor, Benedict of Aniane, Louis implemented monastic reforms that attempted to standardize monastic life in the empire. The reforms were intended to establish a uniform monastic practice in an empire in which a variety of monastic rules were followed. The reforms, implemented in 816-817, introduced the Rule of Benedict of Nursia, or at least Benedict of Aniane's understanding of it, as the standard rule of the empire. Louis's reform legislation also sought to improve further the morality and education of the clergy.Louis's political and religious reforms were not uniformly popular in the empire, and in 817 a revolt broke out that affected the shape of the emperor's reign. His nephew, Bernard, king of Italy, with the support of bishops and nobles, revolted against the settlement of 817. Louis quickly, and ruthlessly, suppressed the revolt. Bernard was sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to blinding-a particularly unpleasant punishment that led to Bernard's death soon after it occurred. The nobles were exiled, and the bishops, including Theodulf of Orléans, were deposed from their sees. Four years after the revolt, in 821, Louis issued a general amnesty, recalling and restoring the exiles and bishops. As part of this reconciliation, Louis underwent voluntary penance for the death of Bernard. Although the act, undertaken from a position of strength, was regarded as meritorious at the time, it set a bad precedent for later in Louis's reign.Louis clearly made substantial improvements on the organization of the empire and on Carolingian relations with Rome in the first half of his reign, but in the second half he suffered from the revolts of his sons and the near collapse of the empire. The difficulties Louis faced were the result, in part, of his second marriage to Judith, a member of the Welf family, which had extensive holdings in Bavaria and other parts of Germany. The birth of a son on June 13, 823, the future Charles the Bald, and the promotion of Bernard of Septimania further complicated matters for Louis. He also suffered from the death of his closest advisor, Benedict of Aniane, in 821. These problems were made more serious by the ambitions of Louis's older sons, especially Lothar, as well as those of the nobility, who could no longer count on the spoils of foreign wars of conquest to enrich themselves or their reputations. In fact, the end of Carolingian expansion, with the exception of missionary activity among the Danes and other peoples along the eastern frontier, limited the beneficence of the Carolingian rulers and allowed the warrior aristocracy to exploit the tensions within the ruling family for their own gain.The situation came to a head in the late 820s and early 830s and led to almost ten years of civil strife throughout the empire. A revolt broke out in 830 after Louis had promoted Bernard of Septimania to the office of chamberlain and granted territory to Charles in the previous year. With the support of various noble factions, the older sons of Louis rebelled against their father in April and accused Bernard and Judith of adultery, sorcery, and conspiracy against the emperor. Lothar, although not originally involved, joined the rebellion from Italy and quickly asserted his authority over his younger brothers. Lothar took his father and half-brother into custody, deposed Bernard, who fled, and sent Judith to a convent. But his own greed disturbed his brothers, who were secretly reconciled with their father. At a council in October, Louis rallied his supporters and took control of the kingdom back from Lothar. Judith took an oath that she was innocent. Louis reorganized the empire, dividing it into three kingdoms and Italy, which Lothar ruled. The sons of Louis would rule independently after their father's death, and no mention of empire was made in this settlement.Although Louis was restored, the situation was not resolved in 830, and problems remained that caused a more serious revolt in 833-834. Along with the question of how to provide for Charles, the problem of the ambitions of Lothar and his brothers remained, as did that of an acquisitive nobility. Furthermore, certain leading ecclesiastics, including Agobard of Lyons and Ebbo of Rheims, argued that Louis had violated God's will by overturning the settlement of 817 when he restructured the plan of succession in 830.The older sons formed a conspiracy against their father that led to a general revolt in 833. Meeting his sons and Pope Gregory IV (r. 827-844) at the so-called Field of Lies, Louis was betrayed and abandoned by his army and captured by his sons. Once again, the emperor was subjected to humiliating treatment at the hands of Lothar. Judith was sent to Rome with the pope, and both Charles and Louis were sent to monasteries. In October Lothar held a council of nobles and bishops at which Louis was declared a tyrant, and then Lothar visited his father in the monastery of St. Médard in Soissons and compelled Louis to "voluntarily" confess to a wide variety of crimes, including murder and sacrilege, to renounce his imperial title, and to accept perpetual penance. Lothar's actions, however, alienated his brothers Louis and Pippin, who rallied to their father's side. In early 834 Louis the German and Pippin revolted against their brother and were joined by their father, who had regained his freedom. Lothar was forced to submit and returned in disgrace to Italy. In 835 Louis made a triumphant return. He was once again crowned emperor, by his half-brother Bishop Drogo of Metz, and he restored Judith and Charles to their rightful places by his side. The bishops who had joined the revolt against Louis were deposed from their offices by Louis at this time.Louis remained in power until his death, but his remaining years were not peaceful ones; familial tensions remained. It was important to Louis, and especially to Judith, that Charles be included in the succession, but Louis recognized at the same time that it was necessary not to alienate his other sons too completely in the process. And, of course, Lothar's ambitions remained even though he remained out of favor for several years after 834. Louis faced further revolts from Louis the German as well as the son of Pippin; after Pippin died in 838, his portion of the realm was bestowed on Charles rather than Pippin's own heirs. One of Louis's last important acts was his reconciliation with Lothar, who pledged his support for Charles and was rewarded with the imperial title. Louis also divided most of the empire between Lothar and Charles, an act that almost certainly guaranteed further civil war after Louis's death on June 20, 840.Despite the very real break-up of the empire in the generation after his death, Louis should not be blamed for the collapse of the Carolingian Empire, which had revealed its flaws already in the last years of Charlemagne's life. Louis's reign, particularly the first part before 830, was a period of growth for the empire, or at least the idea of empire. In fact, his elevation of the idea of empire as the ultimate political entity and his own understanding that the empire was established by God was a significant advancement in political thought and remained an important political idea for his own line and for the line of his successors. His codification of Carolingian relations with Rome was equally important, creating a written document that strengthened and defined imperial-papal ties for the ninth and tenth centuries. Although he faced difficulties in the last decade of his life that prefigured the break-up of the empire in the next generation, Louis was a farsighted ruler, whose reign provided many important and lasting contributions to early medieval government and society.See alsoBenedict of Aniane; Carolingian Dynasty; Carolingian Renaissance; Charlemagne; Charles the Bald; Louis the German; Ordinatio Imperii; Pippin III, Called the ShortBibliography♦ Cabaniss, Allen, trans. Son of Charlemagne: A Contemporary Life of Louis the Pious. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1961.♦ Ganshof, François Louis. The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy. Trans. Janet Sondheimer. London: Longman, 1971.♦ Godman, Peter, and Roger Collins, eds. Charlemagne's Heir: New Perspectives on the Reign of Louis the Pious. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.♦ Halphen, Louis. Charlemagne and the Carolingian Empire. Trans. Giselle de Nie. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1977.♦ McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751-987. London: Longman, 1983.♦ Noble, Thomas X. F. The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680-825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.♦ Scholz, Bernhard Walter, trans. Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Emperor Louis the Pious in the dress of a Christian Roman ruler from Hrabanus Maurusis (Rome, Vatican Library)Equally important steps were taken by Louis to reorganize and strengthen relations with the pope in Rome. In 816 he was crowned by Pope Stephen IV in the city of Rheims, a coronation that has traditionally been seen as a concession to papal authority and an abdication of sovereignty. Louis, in fact, gave nothing up by accepting coronation from Stephen, but merely solidified relations between the pope and emperor and confirmed what was implicit in the coronation of 813. Furthermore, because the pope was the highest spiritual power and the representative of Peter, the great patron saint of the Carolingians, it was only logical that Louis should receive papal blessing. But more important than the coronation was the new constitutional and legal settlement that Louis imposed on Rome in two stages, in 816/817 and 824. Starting with the unwritten rules that had guided relations between the Carolingians and the pope for the previous two generations, Louis issued the Pactum Ludovicianum in 816 and confirmed it the following year with the new pope, Paschal I. This document identified the territories under papal control and precisely defined the relationship between Rome and the Frankish rulers. Although recognizing papal autonomy, the pact proclaimed the duty of Carolingian rulers to protect Rome. This agreement provided a written basis for the relationship between the pope and the Carolingian emperors and regularized the relationship between them by incorporating it into traditional Carolingian governmental structures.An even greater step in the development of the relationship between Louis and Rome occurred with the publication of the Constitutio Romana in 824. In 823, following a period of turmoil in Rome involving the pope and high-ranking officials of the city's administration, Lothar, acting as his father's representative, issued the Constitutio, which confirmed the long-standing relationship between the Carolingian rulers and the popes. The Constitutio was intended to protect the pope and people of Rome and to provide a clear written framework for the place of Rome in the empire. The Constitutio stated the obligation of the pope to swear on oath of friendship to the emperor after his election as pope but before his consecration. The people living in the papal territories were also to swear an oath of loyalty to the emperor. The Carolingians claimed the right to establish courts in Rome to hear appeals against papal administrators. The Constitutio summarized, in writing, the customary rights and obligations of three generations of Frankish rulers, providing a more solid foundation for the exercise of Carolingian power in Italy.Louis also instituted important reforms of the church in his empire during his reign as emperor, building upon reforms that were begun while he was still king of Aquitaine. With his close friend and advisor, Benedict of Aniane, Louis implemented monastic reforms that attempted to standardize monastic life in the empire. The reforms were intended to establish a uniform monastic practice in an empire in which a variety of monastic rules were followed. The reforms, implemented in 816-817, introduced the Rule of Benedict of Nursia, or at least Benedict of Aniane's understanding of it, as the standard rule of the empire. Louis's reform legislation also sought to improve further the morality and education of the clergy.Louis's political and religious reforms were not uniformly popular in the empire, and in 817 a revolt broke out that affected the shape of the emperor's reign. His nephew, Bernard, king of Italy, with the support of bishops and nobles, revolted against the settlement of 817. Louis quickly, and ruthlessly, suppressed the revolt. Bernard was sentenced to death. His sentence was commuted to blinding-a particularly unpleasant punishment that led to Bernard's death soon after it occurred. The nobles were exiled, and the bishops, including Theodulf of Orléans, were deposed from their sees. Four years after the revolt, in 821, Louis issued a general amnesty, recalling and restoring the exiles and bishops. As part of this reconciliation, Louis underwent voluntary penance for the death of Bernard. Although the act, undertaken from a position of strength, was regarded as meritorious at the time, it set a bad precedent for later in Louis's reign.Louis clearly made substantial improvements on the organization of the empire and on Carolingian relations with Rome in the first half of his reign, but in the second half he suffered from the revolts of his sons and the near collapse of the empire. The difficulties Louis faced were the result, in part, of his second marriage to Judith, a member of the Welf family, which had extensive holdings in Bavaria and other parts of Germany. The birth of a son on June 13, 823, the future Charles the Bald, and the promotion of Bernard of Septimania further complicated matters for Louis. He also suffered from the death of his closest advisor, Benedict of Aniane, in 821. These problems were made more serious by the ambitions of Louis's older sons, especially Lothar, as well as those of the nobility, who could no longer count on the spoils of foreign wars of conquest to enrich themselves or their reputations. In fact, the end of Carolingian expansion, with the exception of missionary activity among the Danes and other peoples along the eastern frontier, limited the beneficence of the Carolingian rulers and allowed the warrior aristocracy to exploit the tensions within the ruling family for their own gain.The situation came to a head in the late 820s and early 830s and led to almost ten years of civil strife throughout the empire. A revolt broke out in 830 after Louis had promoted Bernard of Septimania to the office of chamberlain and granted territory to Charles in the previous year. With the support of various noble factions, the older sons of Louis rebelled against their father in April and accused Bernard and Judith of adultery, sorcery, and conspiracy against the emperor. Lothar, although not originally involved, joined the rebellion from Italy and quickly asserted his authority over his younger brothers. Lothar took his father and half-brother into custody, deposed Bernard, who fled, and sent Judith to a convent. But his own greed disturbed his brothers, who were secretly reconciled with their father. At a council in October, Louis rallied his supporters and took control of the kingdom back from Lothar. Judith took an oath that she was innocent. Louis reorganized the empire, dividing it into three kingdoms and Italy, which Lothar ruled. The sons of Louis would rule independently after their father's death, and no mention of empire was made in this settlement.Although Louis was restored, the situation was not resolved in 830, and problems remained that caused a more serious revolt in 833-834. Along with the question of how to provide for Charles, the problem of the ambitions of Lothar and his brothers remained, as did that of an acquisitive nobility. Furthermore, certain leading ecclesiastics, including Agobard of Lyons and Ebbo of Rheims, argued that Louis had violated God's will by overturning the settlement of 817 when he restructured the plan of succession in 830.The older sons formed a conspiracy against their father that led to a general revolt in 833. Meeting his sons and Pope Gregory IV (r. 827-844) at the so-called Field of Lies, Louis was betrayed and abandoned by his army and captured by his sons. Once again, the emperor was subjected to humiliating treatment at the hands of Lothar. Judith was sent to Rome with the pope, and both Charles and Louis were sent to monasteries. In October Lothar held a council of nobles and bishops at which Louis was declared a tyrant, and then Lothar visited his father in the monastery of St. Médard in Soissons and compelled Louis to "voluntarily" confess to a wide variety of crimes, including murder and sacrilege, to renounce his imperial title, and to accept perpetual penance. Lothar's actions, however, alienated his brothers Louis and Pippin, who rallied to their father's side. In early 834 Louis the German and Pippin revolted against their brother and were joined by their father, who had regained his freedom. Lothar was forced to submit and returned in disgrace to Italy. In 835 Louis made a triumphant return. He was once again crowned emperor, by his half-brother Bishop Drogo of Metz, and he restored Judith and Charles to their rightful places by his side. The bishops who had joined the revolt against Louis were deposed from their offices by Louis at this time.Louis remained in power until his death, but his remaining years were not peaceful ones; familial tensions remained. It was important to Louis, and especially to Judith, that Charles be included in the succession, but Louis recognized at the same time that it was necessary not to alienate his other sons too completely in the process. And, of course, Lothar's ambitions remained even though he remained out of favor for several years after 834. Louis faced further revolts from Louis the German as well as the son of Pippin; after Pippin died in 838, his portion of the realm was bestowed on Charles rather than Pippin's own heirs. One of Louis's last important acts was his reconciliation with Lothar, who pledged his support for Charles and was rewarded with the imperial title. Louis also divided most of the empire between Lothar and Charles, an act that almost certainly guaranteed further civil war after Louis's death on June 20, 840.Despite the very real break-up of the empire in the generation after his death, Louis should not be blamed for the collapse of the Carolingian Empire, which had revealed its flaws already in the last years of Charlemagne's life. Louis's reign, particularly the first part before 830, was a period of growth for the empire, or at least the idea of empire. In fact, his elevation of the idea of empire as the ultimate political entity and his own understanding that the empire was established by God was a significant advancement in political thought and remained an important political idea for his own line and for the line of his successors. His codification of Carolingian relations with Rome was equally important, creating a written document that strengthened and defined imperial-papal ties for the ninth and tenth centuries. Although he faced difficulties in the last decade of his life that prefigured the break-up of the empire in the next generation, Louis was a farsighted ruler, whose reign provided many important and lasting contributions to early medieval government and society.See alsoBenedict of Aniane; Carolingian Dynasty; Carolingian Renaissance; Charlemagne; Charles the Bald; Louis the German; Ordinatio Imperii; Pippin III, Called the ShortBibliography♦ Cabaniss, Allen, trans. Son of Charlemagne: A Contemporary Life of Louis the Pious. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1961.♦ Ganshof, François Louis. The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy. Trans. Janet Sondheimer. London: Longman, 1971.♦ Godman, Peter, and Roger Collins, eds. Charlemagne's Heir: New Perspectives on the Reign of Louis the Pious. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.♦ Halphen, Louis. Charlemagne and the Carolingian Empire. Trans. Giselle de Nie. Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1977.♦ McKitterick, Rosamond. The Frankish Kingdoms under the Carolingians, 751-987. London: Longman, 1983.♦ Noble, Thomas X. F. The Republic of St. Peter: The Birth of the Papal State, 680-825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1984.♦ Scholz, Bernhard Walter, trans. Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's History. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1972.

Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe. 2014.